From Vision to Implementation: Addressing Structural Barriers in Infrastructure Delivery

A perspective on the structural barriers that slow infrastructure and energy project delivery, and the importance of aligning policy, capital, and execution to enable sustainable outcomes.

1/13/20264 min read

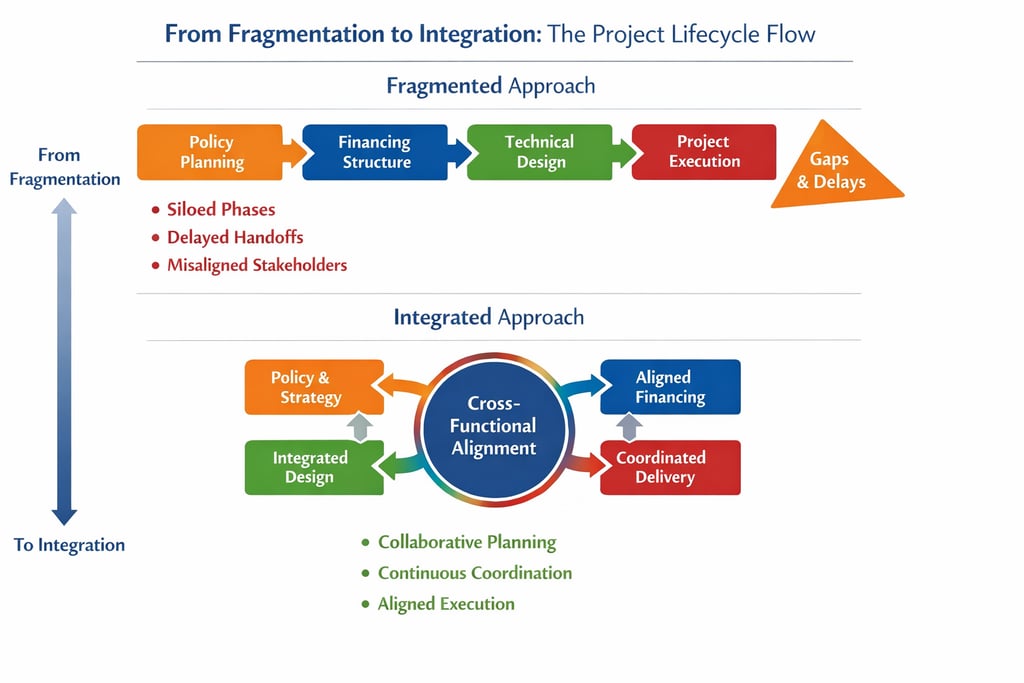

In emerging markets, infrastructure and energy projects are critical to economic resilience, energy security, and climate goals. Strategic plans and policy ambitions are clear, yet many projects stall or fail to progress beyond early development. The problem is not ambition or technical skill, but persistent misalignment across the project lifecycle.

A Real-World Illustration: The Cost of Misalignment

This pattern is increasingly observed across large-scale infrastructure and renewable energy initiatives in Southeast Asia. Projects with strong policy backing and clearly articulated environmental targets have nonetheless experienced prolonged delays due to early-stage misalignment between regulatory objectives, financing structures, and stakeholder engagement. Only when a cross-functional team connected regulators, investors, and local authorities did the project move forward, showing the value of early, systemic alignment.

Structural Misalignment as the Core Constraint

Structural misalignment is the core constraint facing infrastructure delivery. Multiple decision-making layers, each with distinct mandates, timelines, and risk tolerances, must be brought into early alignment; without this, project momentum inevitably weakens over time.

A core challenge arises from policy–finance misalignment, where regulatory objectives are not translated into frameworks that make sense to investors, leaving a gap between policy intent and financial viability. Compounding this are feasibility limitations: studies may focus more on securing approvals than on ensuring long-term operational success, undermining sustainability from the outset. Stakeholder sequencing gaps also emerge when critical partners are brought in only after key parameters are set, diminishing collaboration and shared ownership. Finally, execution discontinuities, particularly during the shift from concept to delivery, can further erode project momentum and continuity.

Rather than being tackled systemically, these issues are too often addressed in isolation. The result is a pattern of incremental adjustments, rather than the durable progress needed for effective infrastructure delivery.

Infrastructure as a Coordinated System

Infrastructure projects should be understood not as isolated decisions, but as coordinated systems that span the full spectrum from policy formulation and capital structuring to technical design, delivery, and ongoing operations. When each phase is treated as a standalone exercise rather than as part of an integrated process, a series of downstream constraints can arise.

For instance, early policy decisions may unintentionally restrict available financing options, limiting the flexibility required for effective project delivery. Similarly, risk can be transferred between parties rather than properly mitigated, increasing project vulnerabilities and the potential for conflict. Diffused accountability across institutions further complicates matters, making it difficult to maintain clear oversight and responsibility throughout the project lifecycle. Ultimately, in complex and capital-intensive projects, this kind of fragmentation undermines adaptability and heightens the risk of delays.

Limitations of Phase-Based Delivery Models

Conventional phase-based models assume that, as a project progresses from planning to financing and then to execution, major uncertainties will have been resolved. Yet in practice, unresolved policy, financial, and stakeholder issues often resurface later. This recurring emergence of unresolved issues creates a cascade of challenges.

Repeated restructuring of project parameters is a common consequence, disrupting both project flow and planning efforts. Extended negotiation cycles may also arise, slowing progress and delaying implementation. As a result, investor confidence can be eroded and institutional continuity disrupted, both of which are critical for successful project delivery. Attempting to accelerate timelines without first addressing these fundamental issues often compounds risk, rather than reducing it.

Enablers of Effective Project Progression

Projects that advance consistently tend to share several enabling characteristics. Most notably, they achieve early alignment between policy objectives and financing structures, ensuring that financial mechanisms are designed to support regulatory goals from the very beginning. These projects also prioritize feasibility assessments grounded in operational and lifecycle considerations, which lay a realistic foundation for long-term success. Deliberate and carefully sequenced stakeholder engagement further enhances collaboration and fosters a strong sense of project ownership. In addition, maintaining clear institutional ownership throughout all development stages strengthens accountability and ensures continuity. While these elements do not eliminate the inherent complexity of infrastructure delivery, they provide a robust framework for managing it effectively.

The Consultant’s Role: Facilitating Integration and Alignment

Consultants have a unique vantage point in these environments. By diagnosing sources of misalignment early and designing integrative frameworks, consultants can facilitate cross-institutional coordination, mediate between stakeholders, and support the development of robust, adaptable project delivery models. Their contribution lies not only in technical or financial expertise, but in enabling the disciplined collaboration that underpins lasting success.

Among public authorities, financiers, technical advisors, and operators, there is often a notable gap in integrative capacity. Bridging this gap requires an effective integrative function, one that translates policy intent into implementable structures and bridges the divide between vision and practical application. Such a function also aligns stakeholder expectations across sectors, fostering cooperation and minimizing the risk of miscommunication. Importantly, it maintains continuity from early development through to project delivery, helping to sustain momentum throughout the entire project lifecycle. This integrative role becomes especially critical in cross-border and emerging-market contexts, where regulatory frameworks are evolving and financing expectations can differ significantly.

Key Lessons for Practitioners

To improve infrastructure project outcomes:

1. Prioritize early, cross-functional alignment by bringing policymakers, financiers, technical teams, and end users together at the outset.

2. Embed integrative functions across the project lifecycle through roles or teams dedicated to translating policy into action and ensuring continuity.

3. Maintain institutional clarity and accountability, assigning clear ownership for each phase and preventing responsibilities from becoming diffused.

4. Center feasibility on operational realities by evaluating lifecycle costs, operational risks, and stakeholder capacity from the start.

By identifying and addressing misalignments early, supporting robust frameworks for collaboration and accountability, and embedding these principles throughout the project lifecycle, consultants can help bridge the gap between vision and execution, delivering infrastructure projects that not only launch, but endure.

The observations outlined here reflect commonly encountered implementation dynamics across infrastructure and energy initiatives in emerging markets.

Ezra & Macquarie - Project lifecycle: fragmentation to integration

© 2008 – 2026 Ezra & Macquarie Group. All rights reserved. Powered by Britannia Ventures.

A strategic advisory and technical solutions firm helping governments, corporations and investors across Asia shape strategy, de-risk execution and deliver measurable impact.

Our Services

Company